Sunday, August 27, 2017

Wild Beyond Belief! A review of those crazy 60s and 70s indies

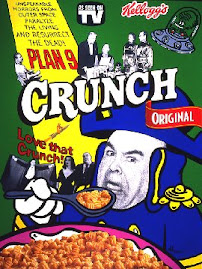

Fellow cult film nerds, wouldn't you love to go back in time and witness what we obsess over? How cool would it be to buy a ticket in 1928 and watch "London After Midnight" or "Heart Trouble"? Both apparently long lost. Or what about dipping into a theater and seeing "Dracula" on opening day? Or maybe head 25 years into the future and catch Ed Wood in a tiny studio helming "Plan 9 From Outer Space," or dip into a drive in or Saturday late night cinema show in the '60s and '70s to catch "Incredibly Strange Creatures ...," "Dracula Versus Frankenstein," "Cain's Cutthroats," "Bigfoot," "Spider Baby," ... some readers have probably enjoyed these later-times bucket lists.

But, for most of us, all we have are the genre books to understand what it was like to be in on the genesis of cult films and cult genres. "Wild Beyond Belief: Interviews with Exploitation Filmmakers of the 1960s and 1970s" (www.mcfarlandpub.com ... here ... 800-253-2187) takes you into the world of the very small budget films of that era. Many of the players, from the lesser known (Jenifer Bishop, Ross Hagen, Joyce King ...) to the more famous (Jack Hill, Sid Haig, Al Adamson, Sam Sherman ...) recollect their experiences creating films such as "Blood of Dracula's Castle," "Spider Baby," "The Hellcats," "The Thing With Two Heads," "The Mighty Gorga," ... and so many more.

The interviewer, and author of this McFarland offering, is Brian Albright, a well-known name in genre writing. I really enjoyed his more recent book "Regional Horror Films: 1958-1990" and reviewed it here. Albraight manages to capture the era, the slap-dash, get-it-shot-and-put-it-together urgency of indy movie making in that era. Films such as "Gallery of Horrors" and "The Female Bunch" couldn't rely on video or DVD sales, or inclusions on streaming services like NetFlix to make money. They had to get into the theaters, in the drive-ins, often as a third feature, or on 42nd Street, to make those dimes. Penny-pinching was not an exception; it was the norm.

One interviewee relates to Albright how only $50 was coming in a week for the work, less than what was promised. But the interviewee was still happy, because pay was actually occurring! Not getting paid was a reality to the cast and crew of these films.

Many personalities flit through these interviews though they were not interviewed. Jack Nicholson, Roger Corman, Bruce Dern, Jill Banner, Carol Ohlmart, Harry Dean Stanton, John Carradine, Lon Chaney Jr., Mantan Moreland, Dennis Hopper, Scott Brady, etc. It's a reminder that many famous actors moved through both the big-budget and the micro-budget films, or that many big names rubbed shoulders with low-budget directors as their stars fell. And many stars started their careers in the basement.

Spahn's Ranch, the California, Nevada and Utah deserts, Bronson Canyon, a castle an hour or so away from Hollywood, crew members volunteering to take bit acting parts in the films, penny-pinching directors surrounded by talented but still-starving actors and crew members (think Vilmos Zsigmond) producing films so uniquely bizarre that they have survived longer in memory and fondness than the bigger-budget studio films of the same eras. (That's a mouthful of a sentence-paragraph, I admit).

Sam Sherman, in his interview, notes that the success of these indie low-budget films prompted calls from the bigger studios asking to share space on the screens. One example he recalls was the producers of "The Molly Maguires" requesting "Satan's Sadists" to play on the same bill. But, as Sherman notes, eventually the majors learned that they could produce the same type of films, such as "Halloween," for low budgets and usually better production values. That signaled the beginning of the end.

"Wild Beyond Belief" is an homage to an era that really doesn't exist anymore. Thanks to technology, even the derivative cheapie horror duds that debut on Netflix or Amazon Prime are slicker than the '60s films made by a David Hewitt or Adamson.

But they lack what these oldies have -- heart and a unique style, for better or worse. That's why we love them, and we're so happy that writers like Albright have taken the time to collect and preserve its memories. This book (its Amazon page is here) is an excellent companion to Fred Olen Ray's "The New Poverty Row ..."

Sunday, August 13, 2017

Enjoy The Monster Movies of Universal Studios

Book review by Doug Gibson

I really enjoy reading "The Monster Movies of Universal Studios," Rowman & Littlefield, June 2017, the latest film genre offering from the prolific James L. Neibaur (an Amazon link is also included). This book is not as deep a dive as "Universal Horrors: The Studio's Classic Films, 1931-1946," from Tom Weaver and Michael and John Brunas. But it's not intended to be that comprehensive.

Neibaur focuses on only the monster movies, with Dracula, the Mummy, Invisible Men and Women, the Frankenstein Monster, Wolf men and a woman, and the 1950's Creature From the Black Lagoon. He also includes the Abbott & Costello monster comedies.

While I have to confess I probably would have preferred chapters from Neibaur on the early Universal films "Murders in the Rue Morgue," "The Black Cat" and "The Raven" instead of a couple/or three of the so-so Invisible Man sequels, I was impressed by the research and smooth writing skills of the author, which have become a staple of his books, the most recent (at least I read) a take on WC Fields' films and soon to come is one on Andy Clyde's Columbia shorts --- sheer manna for us!

Twenty-nine films are assessed, starting with "Dracula" and ending with "The Creature Walks Among Us." Generally, the chapters start with an info box cover, the genesis of the films from conception to planning -- who writes scripts, who directs, the cast assembled -- with a synopsis of the film. Also covered are budgets, how the filming went, how the film was received both critically and financially, what was planned for the future, and the author's assessment of the film. Neibaur has gathered film reviews and exhibitor assessments of the period, and includes sourced quotes, mostly from film participants.

As I mentioned, this is not as detailed as "Universal Horrors" but even that will make it a perhaps more relaxed read for the more casual films of the genre. As the father of a 12-year-old son who, thanks to my efforts, loves the old Universal horrors, he's soon to read "The Monster Movies of Universal Studios," while a turn at the larger "Universal Horrors ..." is still a few years away.

And there is fun, interesting information gathered by Neibaur. For example, a young Betty Grable was considered for the female lead in both "Dracula" and "Frankenstein." She didn't quite pass muster, though. In the early 1940s, Universal really trimmed its budgets. "The Mummy's Hand," for example, was made for a mere $80,000! In fact, as Neibaur notes, the films generally easily made money due to the parsimony of the studio. Also, an angry Bela Lugosi, in his more prosperous first half of the 1940s, swore never to work for Universal again. That would change as he gladly accepted his iconic role with Abbott & Costello a few years later. Another interesting tidbit is that Lou Costello was convinced "Abbott & Costello Meet Frankenstein" would be an unfunny box office failure. So sure was he, Neibaur notes, that he seemed annoyed that it was a success.

One more thing that gets across in the book is that Neibaur generally both loves and has great respect for these films with now-iconic monsters. There's none of the snark that occasionally can sour a good read about this genre. About the only film that gets a solid pan is "She Wolf of London," which frankly merits it, since it's a -- in my opinion -- shallow attempt to capture the spirit of Val Lewton.

There are a few typos in the book that could be fixed with another edition or at least e-book or Kindle. An example is Universal spelled as Universale in some chapters. But it's a fact-filled, genre-fun read of a piece of Hollywood history that so many cult film fans love. It merits real estate in your book case. And, trust me, it's a relief to read about Boris Karloff as the Mummy after watching that dreadful Tom Cruise Dark Universe film release.

.

Monday, August 7, 2017

Hammer's sexy vampire film 'Twins of Evil'

Review by Doug Gibson

"Twins of Evil," Hammer's 1971 tales of Count Karnstein turning one part of a lovely pair of twins into a vampire, is not as impressive as other Carmilla-themed films, such as "Lust For a Vampire," or "The Vampire Lovers," but nevertheless it retains its status as a classic due to star Peter Cushing's strong performance as Gustav Weil, fanatical vampire hunter, so enslaved by the mysogyny of his faith and his fear of the undead that he'll solemnly burn to death any young woman who doesn't act normal. The opening scene, where Weil and his brotherhood abduct and burn a young girl to death, indicts Weil as a dangerous fanatic, a man not safe with young women and their instinctive sexuality.

Appropriately, Weil's eagerness to burn female flesh provides righteous indignation for viewers. Yet Cushing is no Matthew Hopkins, as portrayed by Vincent Price in "Witchfinder General." Weil is no hypocrite nor a luster of his victims, nor is he a man who revels in his evil acts. He's a fervent believer in the Old Testament "thou shall not suffer a witch to live." Cushing's Weill, while acting with a maniacal religious fervor, believes he is freeing his victims, releasing them from vampirism to a life with Christ. Late in the film, when it slowly dawns on Cushing that he may have been too zealous, that some of his victims were indeed innocent, his pain and remorse is evident. As both atonement and revenge, he fails to protect himself as he goes after the evil count.

"Twins of Evil" is a prequel to the Carmilla story and films. The evil Count Karstein (Damien Thomas) is tired of the limits to pleasure and evil he can attain as a mortal. He summons an ancestor vampire, Countess Mircella, (Katya Wyeth) who turns him into a vampire. Eager to satiate his lusts and increase his evil, he sets his sights on two gorgeous twins who have moved to Karnstein from Venice to live with Weil and his wife, Katy, (Kathleen Bryon). The twins are portrayed by Playboy models Mary and Madeleine Collinson. Mary plays Maria Gellhorn and Madeleine is her twin Frieda. Maria is the more timid, pious twin. Frieda is rebellious, furious with her uncle Gustav and eventually is drawn to Count Karstein, who willingly becomes a vampire. There is a subplot where Anton, a liberal teacher at the girls' school, is attracted to Frieda. Anton and Gustav, not surprisingly, clash over the latter's vampire hunting. The film climaxes with a hunt for Frieda and the ensuing possibility that the virtuous Maria may pay for her sins.

As I have mentioned, it's easy to hate the fanatical, misogynous Gustav, but he does have one fact to rest on: there are vampires out there stealing the souls of the innocent. Midway through the film, it's a testament to Cushing's acting skills that the audience starts to root for him as he goes after Frieda and the Count. The Collinswood twins are gorgeous. They are not trained actors, and it shows in their performances. Madeleine does a better job than her sister Mary, but that may be only because she as the meatier role as the bad Frieda. The print I saw has very little nudity. The most explicit scene is where Frieda, pretending to be the innocent Maria, attempts to seduce and bite schoolteacher, Anton.

The Karnstein saga was a Hammer trilogy that, as mentioned, includes "Lust for a Vampire" and "The Vampire Lovers." This is intended to be the first chapter. Watching these movies is a pleasant reminder of how vulnerable and difficult it once was to be a vampire. With the constraints of the cross, daytime, coffins, foes such as Van Helsing and Weil, and native soil, one could understand why successful vampires such as Carmilla and Dracula had pride that overlapped into egotism. They had survived through time. Count Karstein and Frieda are, ultimately, not-too-difficult prey for Weil, Anton and others. It remains a constant annoyance to this reviewer that the above-mentioned disadvantages are not a problem for today's "Calvin Klein" vampires that infect films such as "Twilight," "True Blood" and "Being Human" ...

Tuesday, August 1, 2017

The Legacy of George A. Romero (1940 - 2017)

By Steve D. Stones

In honor of the legacy of director George A. Romero, here are five of my most favorite Romero films. Romero's impact on the horror film industry cannot be objectively measured or overstated. Romero was a true maverick loved by those who worked with him. He will be greatly missed.

- Night of The Living Dead (1968). Here is the zombie horror movie that lays the foundation for every zombie movie that follows. A young woman named Barbara is attacked in a Pennsylvania cemetery by a zombie. She finds her way to a small farm house occupied by five other people hiding in the basement. News footage seen on a television gives the film a realistic, documentary feel that continually puts the viewer on the edge of his seat. The occupants of the farmhouse fight for their lives to stay alive. Our hero is an African-American man, Duane Jones, who does not triumph in the end, but makes a strong political statement on the coat tails of Martin Luther King Jr. and the race riots of the 1960s. Remade in 1990.

- The Crazies (1973). Romero continues on with a post-apocalyptic theme seen in Night of The Living Dead, and will continue even further in Dawn of The Dead. Like Night of The Living Dead, this film also has a realistic, documentary feel that leaves the viewer nervous and tense. It shows how our trusted institutions, such as law enforcement, news media and military, can be torn apart in the event of a tragedy. No one is to be trusted or can be turned to in the event of a disaster. A cynical view, but one which permeated American culture in the mid-1970s after President Nixon's resignation. A film which coincides well with the Watergate Era. Also known as Code Name: Trixie. Remade in 2010.

- Martin (1978). This creative film is an interesting take on the vampire myth. Martin is a peculiar young man who has a taste for blood – literally and figuratively. There's just one problem. Martin does not have fangs like a vampire, nor does he sleep in coffins during the day or avoid sunlight. All the established vampire iconography is stripped away in this film. Martin even has to use razor blades to get blood from his victims. Romero has often mentioned Martin as his best film. Many film critics agree.

- Dawn of The Dead (1979). Occurring just a few years after Night of The Living Dead, this film is a direct commentary on the consumer culture of the American lifestyle. Even in death, American zombies have the mind dulling sense to flock to a shopping mall to consume more stuff they cannot afford. The zombie becomes a parody and cartoon character, adding to Romero's critique of consumer culture. The irony here is that the living want it all too, but eventually end up dead because of their greed. We are all mindless zombies who want to consume more and more, in the eyes of Romero's Dawn of The Dead. Remade in 2004.

- Creepshow (1982). An anthology of five short stories in comic book fashion, Romero teamed up with horror writer Stephen King for this installment. The first story, Father's Day, is my favorite of the five. Here, a deceased father exhibits his patriarchal power over his daughter, even from the grave. He crawls his way out of the grave to complain about not getting a Father's Day cake. Actor Ed Harris gets smothered with his tombstone after falling into the grave. The father finishes the day by serving up his daughter's head on a platter. Who could ask for a better Father's Day?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)